“You said a couple weeks ago that the newspaper is going in a direction that you were not comfortable with because of a certain person, I was hoping that this kind of stuff wouldn’t pop up again.”

These astonishing words came straight from Ocean Springs Mayor Kenny Holloway, chastising a local newspaper editor for publishing a story without first getting his approval.

The “certain person” the mayor was speaking about was me.

The conversation took place just weeks after Leigh Coleman, editor and owner of the Ocean Springs Weekly Record, was bombarded with cease and desist letters — not because the newspaper’s reporting was inaccurate, but because it exposed City Hall’s shady dealings.

In the months prior, Coleman was my research partner on several investigations, including the Securix conflict-of-interest saga, working alongside me as we uncovered troubling details about the city’s contracts and backroom dealings.

But when the pressure mounted, Coleman caved to City Hall’s demands — and this reporter was what she often referred to as “the sacrificial lamb.”

A Parting of Ways

Shortly after Coleman and I exposed the Securix scandal — revealing that city officials were personally profiting from an uninsured motorist ticketing program — the legal threats started rolling in. Law firms representing City Attorney Robert Wilkinson bombarded The Record with demand letters.

Notably, none of them claimed our reporting was inaccurate. Instead, they took issue with our decision to quote Securix Chairman and CEO Jonathan Miller — a man Wilkinson happened to be entangled with in litigation at the time.

Coleman told me she couldn’t continue paying the mounting legal fees needed to fend off the letters. After speaking with the very people pressuring her, she said the only solution was to cut professional ties with me. I shifted my focus to GC Wire, while she kept running The Record.

On the surface, our friendship remained intact — we spoke nearly every day — but something had changed. I watched as Coleman grew increasingly cozy with City Hall. She was on friendly terms with officials she had previously scrutinized, including Mayor Kenny Holloway and Wilkinson, the very person who had been threatening her just weeks before.

A Phone Call with the Mayor

Two weeks after I left The Record, Coleman and the mayor had a stunning 51-minute conversation in which Coleman not only reassured the mayor that her newspaper would fall in line, but also actively worked to ingratiate herself within his public relations squad.

She dismissed past reporting, promised to shift the newspaper’s tone to a more flattering portrayal of City Hall, and even pledged to run “fluff” stories instead of investigative journalism.

Along the way, she betrayed not just me, but her own readers — mocking concerned residents, calling the community “disgusting,” offering political strategies, and making it seem as though The Record had transformed from a watchdog into the mayor’s personal PR lapdog.

This call was never supposed to be heard. But now, the public can listen as the mayor and a newspaper editor conspire behind closed doors — shaping coverage, smearing critics, and strategizing how to control the narrative.

What follows isn’t a story about journalism – it’s a backroom deal disguised as media discussion.

Coleman Gets Chastised for Not Following Orders

The call begins with Holloway expressing frustration at Coleman for an article alerting the community that the Ocean Springs Police Chief, Fire Chief, and Community Development Director all departing on the same day. Coleman had already changed the title of the published article prior to the phone call, which originally included the words “Mass Exodus.”

“It was uncalled for before you had talked to anybody that could explain what was going on,” Holloway said, scolding Coleman. He described being caught off guard while attending a lunch in Jackson, only to be approached by people asking what was happening in Ocean Springs. “I’m in Jackson at a lunch, and people are coming up to me and asking me what’s going on at City Hall. I said, ‘What do you mean? They tell me everybody is quitting and leaving.’”

After some discussion, Coleman agrees to suppress future stories until the mayor can sign off. “Now, if you want to, moving forward, if something like this happens again, hopefully not, I will not write anything until I speak to you.”

Still upset that Coleman would write something unflattering about City Hall, the mayor then reminds her of a previous arrangement they had made, referencing my departure from The Record.

“I was thinking and hoping that when you said a couple weeks ago that the newspaper is going in a direction that you were not comfortable with because of a certain person, I was hoping that this kind of stuff wouldn’t pop up again,” Holloway said. Coleman enthusiastically replies, “That’s right. That’s right.”

Coleman was my research partner and co-author of almost all of my articles published on her platform. But during this call, she was leading the mayor to believe she played little to no role, even though she is the newspaper’s editor, publisher, and owner.

The mayor continues to air his displeasure by telling Coleman the Board of Aldermen had not yet been alerted of the departures yet before her article came out, almost as if comparing three officials quitting to notifying the next of kin in a murder.

Listen to the exchange here:

‘Let’s Go Off the Record‘

Throughout her phone call with Mayor Holloway, Coleman can be heard saying “this is off the record” multiple times. It wasn’t always the mayor asking for confidentiality. It was Coleman, unprompted, taking it upon herself to ask questions or give the mayor information she had no intention of sharing with the public – the opposite of what a journalist is supposed to do when speaking with a public official.

The first instance came when she prodded the mayor about the Chief of Police’s early retirement.

“Why did he do that, off the record,” Coleman asked. As the mayor hesitated to answer, Coleman spews, “The community has treated the police terribly.” This would be the first of multiple times she and the mayor would bash residents for voicing their opinions.

“Off the record,” the mayor confirms before suggesting vocal residents might have played a role in the police chief jumping ship. “This whole city is tired and worn out and can hardly do the business of running the city because of all of this social media and all these public records requests,” he added before shifting the conversation to himself.

“And it’s all politically motivated. I could be on Washington and Porter handing out hundred dollar bills and the first one I handed out not turned the right way this group of people would be raising hell.”

Listen here:

‘That’s Good PR Right There!’

Mayor Holloway brings up a security discussion about preventing attacks at local festivals.

Instead of asking follow-up questions — like any journalist would — Leigh Coleman immediately goes for a different angle.

“See, that’s good PR right there!” she exclaims.

Holloway, sensing a safe space, continues: “We do a lot more good in this building than we do bad. Believe me, by a ton.”

Rather than asking about the bad, Coleman reassures him:

“Well, I already told Ravin (mayor’s communications director) to send me good PR. And guess what? Right after that, St. Alphonsus comes to City Hall, a little child is sitting in your seat, you’re smiling — that was a money pic!”

Coleman goes on to complain that no one sent her the picture — as if it was City Hall’s job to provide her with promotional material.

“And nobody gave it to us and I had to dig for it and I did it on my own. She could have folded that together and sent it in as a PR story and it would have been great.”

Listen to “Good PR” here:

‘You Understand We Call that Fluff?’

Leigh Coleman wasn’t interested in holding City Hall accountable. She was interested in “fluff.” And she told Mayor Kenny Holloway that directly.

“Now, off the record completely, I am on Mars right now. If you have anything like a St. Alphonsus visit, any fluff—you understand we call that fluff?” she says. “That’s good news. I think our city needs to hear that.”

The mayor gets the message. “Yeah, we can do that,” he replies.

Coleman then doubles down.

“Stuff like that. It might seem like nothing to you, but that’s what a community newspaper is for.”

Stop right there.

A newspaper’s duty is to inform the public—not to manufacture good press for City Hall. But Coleman wasn’t asking tough questions. She wasn’t asking about infrastructure, transparency, or city finances.

She was asking for fluff.

And she even gives him an example:

“You know that band picture? Let me give you an example, and I’ll let you go. You know when the kids went to London? Social media alone — close to six hundred comments and likes. On the newspaper — thousands of clicks. Fluff works. You got me?”

The message is clear: Leigh Coleman wants the Ocean Springs Weekly Record to be an extension of the mayor’s public relations team.

Listen to the Fluff here:

Those ‘Friggin’ Public Comments

When Leigh Coleman asked Holloway about the controversial East Beach pathway — a project that has sparked heated debate among residents — his response was underwhelming.

“I’m kind of indifferent about it.”

That’s the mayor’s stance on a million plus dollar infrastructure project that could permanently alter one of Ocean Springs’ most beloved areas.

But instead of pressing him — instead of asking how he plans to handle resident concerns or whether the city will listen to the people most affected — Coleman takes a different approach.

“Are ya? Okay, that’s probably a good thing.”

Then, she pivots.

“Cause you got — you know how many lawyers you got ready to sue you?”

Not “What do you say to the people who don’t want this?”

Not “Will you push for community input before moving forward?”

Her only concern was protecting the mayor from lawsuits.

Holloway mentioned that the city was still waiting for approval from the Department of Marine Resources (DMR) on the project. Coleman’s response wasn’t one of a journalist — it was one of a political strategist.

“No, they’re still talking. They’re still going over those friggin’ comments,” she says. The comments she was dismissing were the written comments submitted by residents who live in the area. Instead of representing their voices as an equal part of the story, she reduces their voices to “friggin’ comments” as if they are nothing more than some bureaucratic nuisance getting in the way of development.

Then, she makes her real point — offering the mayor a blunt election-season warning:

“But between me and you and the signpost, and I didn’t say that, if you move forward before the election on that, you’ll lose. Because they’re going to see you got about 10 lawyers ready to sue you if you do something. I’m just reminding you. I know you know it, I’m just saying.”

That’s not a journalist questioning a politician.

That’s an adviser coaching him on how to avoid political damage.

Leigh Coleman is not pushing for transparency. She’s not asking if the mayor has listened to residents. She’s not investigating the legal concerns. She’s warning him to hold off until after the election.

Listen to the salacious advice here:

‘I’m Not Going to Jail Over This’

At one point, the mayor takes an odd change in direction to commiserate about his criticisms, but Coleman is there make sure he knows she has his back.

“Quite frankly, off the record, it’s just aggravating,” Holloway says. “We’re here just trying to do what we were elected to do and hired to do. And, you know, it’s all a conspiracy theory. It’s all about where’s the smoking gun?”

“Well, I have to agree with you. It has been,” Coleman said reassuredly.

The mayor then makes a curious statement that was ripe for a follow-up question: “There is no smoking gun – I told you a while ago, I’m not going to jail over this.”

Of course, the natural response for a reporter is to follow-up by asking: Jail? What could you go to jail over?

But Coleman doesn’t ask. Instead, she belts out a cackling laugh and says, “Listen, off the record, I’m in your corner. I am! I’m not against you. I’m not!”

Listen to it here:

‘Disgusted’ by the Community

The conversation shifted towards the proposed Ocean Springs Police reality TV show that would have aired on the A&E Network. Coleman was a big fan of the idea and wrote a promotional piece for her newspaper. Just before she published, I told her to expect a lot of negativity about this on social media, as people won’t want a COPS type show about their city.

My prediction wasn’t wrong. And Coleman took offense to the opinions of residents. But not before giving Kenny another creepy stroke first.

“I feel like you’ve been giving an unfair shake, I know you have,” Coleman compassionately tells the mayor. “And what happened to the chief and that TV series… what the community said online about the police department made me ill. That’s not supporting your police department at all. That’s terrible… They put their lives on the line. That disgusted me about this community.”

The public reaction to a COPS style TV show was immediate and brutal. Hundreds of residents blasted the idea online. Instead of telling their story in her paper, Coleman chose to lash out at them – the very people her paper is supposed to serve.

Listen here: m8

The Carter Thompson Tapes

Carter Thompson was not a fan of mine. I wrote critical articles of her involvement in the city’s rezoning efforts and she did not appreciate it. However, after she quit her job as the Community Development Director, Thompson reached out to me.

The first contact was a phone call where she blasted city officials and told me about dozens of hours of secret recordings she made during meetings at City Hall. Thompson wanted the recordings published, but with one caveat – Leigh Coleman was to have no part in the writing of the articles.

I spent hours one on one at Thompson’s apartment listening to tapes. On a second visit, I brought a tech guy to help me extract the files from her phone to a thumb drive.

Strangely, Coleman tells the mayor two curious lies during their call: 1) she says it was her that went to Thompson’s home the previous day and 2) that there is nothing on the tapes that is newsworthy. Both claims are laughable.

“After Carter put her keys on the desk and left, she blew up our phones here and we went over there,” Coleman told the mayor. But that simply wasn’t true. I went over to Carter’s apartment. Leigh was not with me. Carter made sure Leigh was not coming with me.

She tells the mayor “we” listened to the tapes at Carter’s for hours. “And I’m listening and I’m like, man, I’m on Kenny’s side,” she says. Ironically, Coleman tells the mayor how crazy she is for recording him without him knowing – as Coleman is quite literally doing the very same thing.

Coleman goes on to give a very detailed account a conversation between her and Carter that never actually took place. She made the whole thing up from fragments of things I told her about the visit. And she got just about all of it wrong.

From this imaginary conversation, Coleman tells Holloway she came to the conclusion there were no problems with the Slaughter and Associates contracts, or any of the other controversies plaguing the mayor and City Hall.

In fact, she tells the mayor Carter Thompson is just a disgruntled employee and praises Holloway for always sounding like a gentleman. The kicker was when she flat out announced her allegiance to the mayor.

“I’m sorry, but after yesterday, your news stories are going to be reflected differently now,” she tells him, making a direct promise that his coverage will improve.

That was another key moment in the abandonment of journalistic ethics. She was no longer a newspaper publisher covering city events, she was a crisis manager. Coleman wasn’t holding the mayor accountable, she was apologizing to him. She was no longer protecting the public’s right to know – she was protecting the mayor’s image.

None of what Coleman describes in this segment actually happened:

.

One more thing about the Carter Thompson tapes. At the time, Leigh and I were still helping each other work through some news stories. While I did not want her to help write an article, I did seek her advice with one particular segment of the recordings.

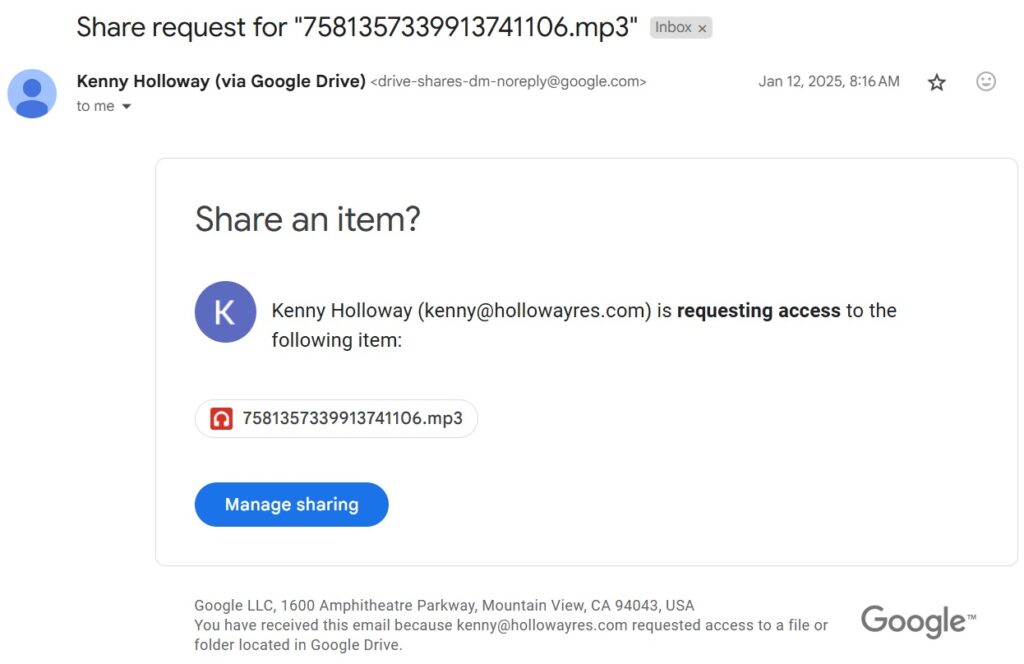

I sent her a file. It was housed on my Google Drive. Her email was the only one with permission to use the link and she was the only one the link was sent to. Coleman called when she received it. We listened to it together and discussed. She assured me nobody else would be privy to the file.

A few hours later, someone tried to click on the download link, which triggered Google to send me a permission request. The request came from… you guessed it, Kenny Holloway.

The very person Coleman and I were investigating, she sneakily tried to send the file to – attempting to give him enough heads up so he could move to damage control.

The OS Record PR Agency

For the remainder of the phone call, Coleman acts as if she is the official PR agent for the mayor and City Hall, beginning by encouraging Holloway to continue avoiding the press.

“We hesitate to answer the phone, because if we say something, how twisted is it gonna get,” the mayor says. “And that’s why we don’t do interviews.” Coleman is cheering along, with repeatedly saying “Yup, yup” and “I get it. That’s right, I get it. That’s right.”

Listen here: m4

Coleman Kills an Important Story

On the call, Leigh Coleman makes a stunning admission: She has abandoned coverage of the Securix scandal entirely.

“I’m done with Securix. I will never write about it again.”

Think about that. A journalist doesn’t decide to “be done” with a major corruption story — unless they’ve been pressured into silence.

She then reassures the mayor that while she won’t be covering it, I will.

“Brian will. He’s not done with it. Off the record — well, it can be on the record — Brian is an excellent researcher and he doesn’t print anything untrue.” But even as she tries to discredit me, she admits the truth: My reporting is factually accurate.

But instead of challenging the mayor with those facts, she goes for a weaker attack, one that is sure to impress her new pal: “The way he presents it is like he wanted to find something and did.”

After that, the mayor points out the one thing he ever found factually wrong in any of my articles. And it was a typo – made by the editor, Leigh Coleman, not me – even though she hands that credit to me in the call. When Coleman published one of my stories, she put the date the Securix contract was signed as 2022, instead of the actual date of 2021.

The typo was fixed quickly after Coleman publishing the article and all articles specifically stated Shea Dobson was mayor when the contract was signed. Holloway was mayor when the program rolled out.

Out of all the reports I have written, that one typo is the only thing Holloway has ever pointed to as being incorrect.

Listen to it here:

.

Coleman wraps up the Securix talk by giving some trailing PR advice: “Just between me and you, I’m done with Securix… I hope you don’t touch that with a 10-foot pole again. You need to get away from that.”

Listen to it here: m6

.

When Mayor Holloway brought up my reporting on the Flock surveillance system, Leigh Coleman immediately played along, despite knowing full well the facts of the story.

“Oh yeah,” she responds — casually dismissing an article she personally helped research and publish.

Holloway then tries to spin the story, falsely claiming that the system was simply an addition to existing cameras.

Coleman knew the truth. She had seen the documents, helped research the system, and knew that the city had buried a $52,000 contract for an advanced operating system — with an additional $24,000 annual cost. She also knew that city officials had lied about it, misrepresenting it as “just cameras” and stating that it simply replaced an old system that had been cancelled.

Yet instead of correcting him, she plays dumb.

“I know. I know that now,” she says, implying that the article was somehow mistaken — even though she knew it wasn’t.

Holloway then pulls out his favorite red herring argument, falsely claiming that my article accused the system of having facial recognition (which it doesn’t).

“We’re not tracking facial expressions or whatever,” the mayor says, deliberately misrepresenting the controversy.

Coleman responds not with a correction, but with unhinged laughter.

Listen to the cackling here:

.

But then Coleman takes it a step further.

“We were talking about the actual system, not the cameras. So it got mixed up. Cameras are good. So, I’m writing another story on cameras being a good thing. Trust me, that’s coming out. That’ll be changed up.”

Let that sink in.

The newspaper’s editor — who knew the original reporting was accurate — was now actively planning to “change up” the story to make it more favorable to City Hall.

That’s not journalism. That’s propaganda.

The Death of a Watchdog

This call was more than just a conversation—it was a confession. A confession that The Ocean Springs Weekly Record is no longer an independent newspaper, but a mouthpiece for City Hall. Leigh Coleman, once an investigative partner, now acts as a gatekeeper for the mayor, ensuring only favorable coverage makes it to print.

The implications are staggering. A city leader openly dictating what a newspaper should and shouldn’t report. A journalist willingly surrendering her independence in exchange for political favor. A once-reliable news source reduced to little more than a PR firm.

For the residents of Ocean Springs, this means one thing: If you’re looking for the truth about your local government, you probably won’t find it in The Record. What you will find is the version of reality City Hall wants you to see.

(Complete call available here.)